Gaps in a language? Well, yes, actually. If people in a particular culture or society never talk about something, or if there’s something they don’t say, then there’s a gap – at least, compared with another culture where they do talk about it. This can be quite a challenge for translators, of course.

Here’s an interesting conversation I had in my student days in Germany in the 1970s: I was sitting in the communal kitchen of my hall of residence, having dinner, when an Iranian student walked past and said:

- Guten Appetit.

- Thank you. How do you say that in Farsi?

- نوش جان (nooshe jan). And how do you say it in English?

- We don’t say anything actually.

- Why not?

- Hm, we seem to have a gap. (I felt tempted to say: “Perhaps it has something to do with our food!”)

Yes, I suppose I might have suggested “Enjoy your meal”, but the truth is that this isn’t a standard – and therefore mandatory – phrase in our culture, whereas in the various European cultures it might be downright rude to walk past someone having a meal and not to say …

- Bon appétit (French)

- Buon appetito (Italian)

- Guten Appetit (German)

- Приятнгого аппетита (Priyatnovo apetita – Russian)

- Смачного (Smachnoho – Ukrainian)

- Smacznego (Polish)

- Eet smakelijk (Dutch)

- Smaklig måltid (Swedish)

So is there a gap in English? Yes, but the gap doesn’t really take shape in our minds until we become aware of it: if we didn’t know that others feel compelled to say something in this situation, we wouldn’t miss it. It’s simply a matter of social conventions – and one culture may have a certain convention, while another doesn’t.

When an English speaker walks into a room and someone else is sitting there, they automatically feel compelled to say “Hello” or something similar. It would be considered rude just to stay silent. However, in other cultures this is perfectly acceptable. I remember a German friend who once looked at me in puzzlement when I said “Hello” to him and then replied: “Wir haben uns doch schon begrüßt!” (“But we said hello earlier on!”)

So let’s look at this gap phenomenon from a translator’s perspective.

Clearly, any translator wanting to see perfect cultural equivalence between the source and the target text, might find this a nightmare, as there is no obvious solution, whereas for a lateral thinker it might be a stimulating challenge: Supposing the Guten Appetit situation comes up in a novel or an advertising text, shall I ignore the gap and put “Enjoy your meal”? Or should I perhaps argue: What’s wrong with a bit of foreignness? After all, the setting is a different culture anyway, and so the reader will expect things to be different; let’s leave the phrase in the original language and add the translation either in brackets or in a footnote. Or – if it’s advertising – should I put something completely different that will speak to the reader more appropriately (i.e. follow the path of transcreation)? Depending on the context, the type of text, the target audience, our brief and the client, any of these solutions may be or may not be appropriate.

An example along similar lines concerns icebreakers which people use casually when they meet in the street. In my home town of Coventry you frequently hear “All right?” – meaning “How are you?” – which rather baffles people from other parts of the country, and it certainly confuses quite a few of our international friends from cultures where you wouldn’t even say “How are you?”, but you’d talk about something completely different:

- Polish: “Co słychać?” (literally: “What is there to listen to?” – meaning: “Any news in your life?”) – And a standard answer might in fact be: “Nic nowego!” (“No news!”)

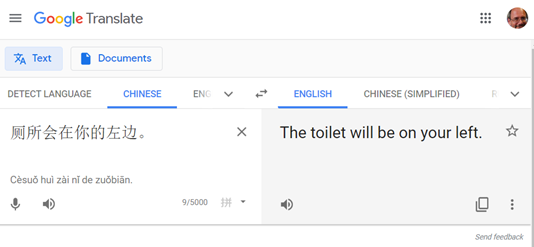

- Mandarin: “你吃了吗?” (Nǐ chī le ma? – “Have you eaten?”).

So the initial chitchat between two Poles and two Chinese people is quite different from what we might expect in an Anglophone culture – and, of course, such cultural differences shouldn’t really come as a surprise: it’s almost trivial to observe that things are done differently in different countries.

Another area that is closely related to social conventions is the field of cultural references. People talk about different things, they do different things, they eat different things, etc. – and this, too, shapes the way they interact, calling for different solutions in a translation, depending on the type of text, the brief, the client, etc.

At times, cultural referencesmay actually be quite easy to translate (or transcreate) if we can find something similar in the target language. For example, in the Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37¾, the author mentions a church lunch where – oh dear! – everyone ends up bringing quiche, a very common English dish (particularly in the 1980s, when the book was written) that can be served cold and is therefore ideally suited for a beige buffet. In the German version – Tagebuch eines frommen Chaoten – the translator, Andreas Ebert, has everyone bringing Kartoffelsalat (potato salad), which has a similar function in German society. However, things aren’t always quite as simple. Our East Asian friends – Chinese, Malaysians, Indonesians – tell us that they would struggle to find a suitable equivalent in their cuisines, as they have a much wider variety of options. So a translator of the quiche incident into Chinese or Malay might be presented with an interesting challenge: too much culinary variety!

Another gap often occurs when we expect no more than superficial cultural equivalence, because the two cultures have different underlying expectations. Take Christmas: Germans enjoy wishing each other Besinnliche Weihnachten – literally: A contemplative Christmas, meaning: a nice peaceful time when you relax, put your feet up and gaze into the candlelight. The phrase is perfectly common on Christmas cards among German businesspeople, but a bit odd in UK! So, depending on my translation client, I may want to put: A peaceful Christmas (which is fairly close to the German), or just very boldly: Merry Christmas (more common and possibly more appropriate – but rather unimaginative and perhaps not very client-friendly).

But there are also gaps arising from lexical differences. Naturally, two cultures (and therefore languages) don’t usually develop along identical routes, and so different catchphrases are bandied about in one society, but not in the other. There’s one German verb I stumble over at least once a week: auf etwas setzen – a phrase that seems to be based on the game of roulette, with the original meaning: “to place one’s chip on a specific number”. However, the phrase has become detached from its original context and is now widely used in the German business community. As there has been no parallel development in the English-speaking world, there is no direct equivalent for the following:

- Wir setzen auf eine klare Fokussierung unseres Geschäfts.

Using the original roulette analogy would give us a totally inappropriate translation:

- We’re putting our bets on a clear focus of our business.

But I doubt if the client would be too happy if I laboured the gambling analogy at this point: It’s not what the author has in mind, and a “clear focus” should really be more than a shot in the dark! Yet any of the following more reasonable translations loses its link to the original metaphor:

- We’ve opted for a clear focus of our business.

- We emphasise a clear focus of our business.

- We rely on a clear focus of our business.

- We believe in a clear focus for our business.

So is there a gap in English? Yes, but only because this metaphorical perspective has no parallel in English, and so we are forced to ignore it.

Finally, a gap can result from different grammatical structures. Take gender equality. Both English and German-speaking countries have had their own grammatical struggles in coping with the issue, but they have had to find different solutions to different problems. Whereas the English-speaking world has focused largely on pronouns (he, she, they), German-speaking authors have been battling with nouns. As Anglophones, we can consider ourselves lucky that the word employee(s) is gender-neutral, while most German speakers would perceive the word Mitarbeiter as totally masculine (both singular and plural), and it has therefore become common to use the rather long-winded phrase Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter (literally female and male employees).[1] On the other hand, some authors – particularly in legal texts – feel that Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter is awkward to read, and they therefore just settle for Mitarbeiter and then apologise – usually in a footnote, such as:

- Aus Gründen der Lesbarkeit wird bei Personenbezeichnungen die männliche Form gewählt, es ist jedoch immer die weibliche Form mitgemeint. (To make this text more readable, the masculine form has been used when referring to persons; however, the feminine form is always implied.)

This gap gives the translator an interesting dilemma. Common sense dictates that we should simply leave the footnote untranslated: after all, it makes no sense with reference to English where we don’t have this problem. It’s only a problem in the German source text (which the target audience isn’t expected to read anyway). On the other hand, our client (who is probably not the final reader) may well insist that if it’s there, it should be translated, regardless of whether it makes sense or not. So what shall we do? Just boldly leave it out? Add a note in the covering email? Translate it but add a translator’s note to the footnote – thus drawing even more attention to it and creating a storm in a teacup? It certainly requires diplomacy and tact.

To sum up, there are indeed gaps we need to be aware of – cases where, as translators, we might want to say something totally different, or where we need to provide an explanation (e.g. in a footnote or bracket), or where it would be best to say nothing at all. There isn’t a clear answer, and our strategy should depend on the context, the type of text, the readership and, of course, the client.

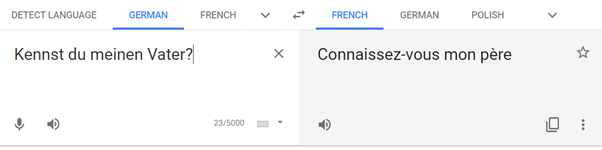

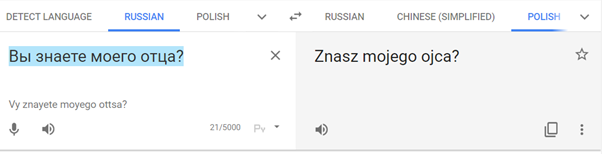

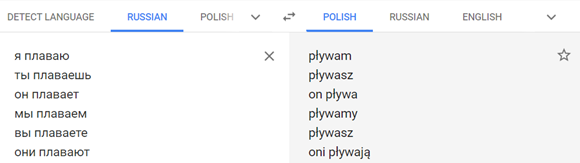

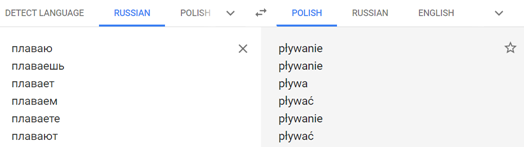

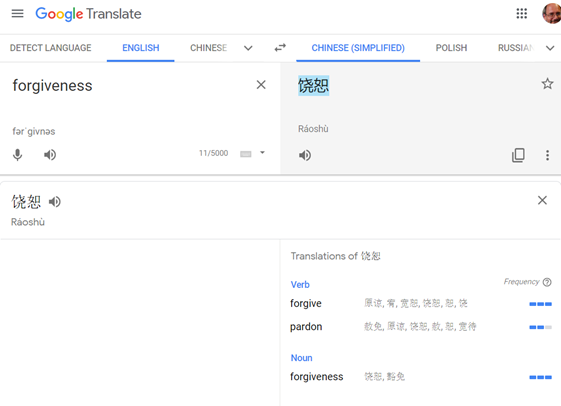

These are decisions that cannot be automated, and the presence of gaps nicely highlights the deficiency of machine translation. A piece of software is always based on the false assumption that something in language A necessarily has at least one equivalent in language B. Yet one of the many things which artificial intelligence cannot do is make creative case-by-case decisions. Try to tell AI to use its loaf and mind the gap: it probably won’t understand what you’re on about – unless it has borrowed the mind of a real human while reading this article.

[1] Other options might be MitarbeiterInnen or Mitarbeiter(innen), but they can be somewhat controversial, as they are often felt to be grammatically awkward or insufficiently respectful towards women, treating them as a mere grammatical add-on.